Master Craftsman Teams. 193

In the early ‘70s F. T. Baker, and Fred Brooks wrote about the notion of Chief Programmer teams. The idea was that a highly skilled chief programer would be assisted by a team of helpers. The chief would write most of the code, delegating simpler tasks to the helpers.

Though the idea was tried at IBM and shown to work well, the idea has never really caught on. One reason may be that the economics don’t appear to be all that good. A team of four juniors making $50K supporting a senior making $100K costs $300K. That just seems like a lot of money for one well supported chief programmer writing most of the code.

But in light of the movement towards software craftsmanship, perhaps it’s time to dust off this old idea and look at it from a different perspective. Consider the following thought experiment…

We are in the throes of a recession that is challenging us to think differently about things. At the same time our universities are raising tuitions and increasing faculty salaries, while requiring ever less from both the faculty and the students. Today’s professors spend about 9 hours per week in the classroom. And the quality of the CS majors graduating from these institutions is, to put it bluntly, wretched.

Why should a young aspiring software professional spend four years and $200K+ to attend an institution that will teach them less about their chosen profession than 3 months of working on a real project with talented mentors? Indeed, why should employers pay $50K for undertrained programmers who are sure to make horrific messes for the next three years of their career?

Consider instead a team of craftspeople. At the center of this team is a master programmer. This is someone who has been programming for two decades or more. This person understand systems at a gut level, and can quickly make technical judgements without agonizing over them. Such a person can direct a team with the kind of calm confidence that only comes with years of experience and seasoning.

Our master has three lieutenant journeymen who themselves each have three apprentices. Our journeymen have at least five years of experience, and are capable both of taking and giving direction. They can make short term tactical decisions, and direct their apprentices accordingly. At the same time they take technical and architectural direction from the master.

The journeymen write a lot of code – almost as much as the master. They also throw away two thirds of the code written by the apprentices, and drive them to redo it better – always better. They teach the apprentices how to refactor, and often pair with them and sit with them while reviewing their code.

The master probably writes more code than any of the team members. This code is often architectural in nature, and helps to establish the seed about which the system will crystalize. The master also sets technical direction and overall architecture, and makes all critical technical decisions. However, the chief job of the master is to relentlessly drive the journeymen towards higher quality and productivity by establishing and enforcing the appropriate disciplines and practices. From the master’s point of view, it’s “my way or the highway.”

Yes, I know this is very anti-scrum. But this is a case where I think scrum in particular, and agile in general just got it wrong. No battle was won by gaining the consensus of the soldiers. And if you don’t think developing a system is a battle against time, resources, and attitudes, then you’ve never built a system. No great team has ever succeeded without a strong coach who imposed discipline, set the vision, and had the final authority over who played and who sat on the bench. Consensus and team rule may be useful tools some of the time, but only in the context of effective leadership.

The apprentices write a significant amount of code—most of which is discarded by the journeymen. The journeymen act as committers. When an apprentice delivers code that the journeyman finds acceptable, the journeyman will commit that code to their main line. Otherwise he sends it back to the apprentice to do over. By the same token the master accepts subsystems from the journeymen and, if acceptable, commits it to the master main line.

The master sees every line of code in the system. The Journeymen see every line of code written by their apprentices, and they write a significant amount themselves. Pairing is prevalent though not universal. Anyone on the team can pair with anyone else. It should not be uncommon for the master to pair with the apprentices from time to time.

Apprentices begin at a young age—perhaps 18 or 19. After all, the idea is that they aren’t going to a university. Rather, the brightest would start as apprentices right out of high school, while others might opt for two years of community college first.

Apprenticeship would last 2-4 years, depending on how quickly the apprentice learns. Apprentices earn no more than minimum wage. After all, they are young, barely productive, and are deriving great benefit from working with experienced journeyman under the guidance of a master.

Attaining journeyman status is something for the master to decide, with advice from the journeymen. The decision is bittersweet because it is a decision to eject the apprentice from the team so that he or she can start the journey. Usually the new journeyman would join the team of a different master.

Some apprentices simply won’t attain journeyman status. In the end, if they fail to make progress, they must be removed from the team. No one should stay an apprentice year after year. It is the responsibility of the journeymen and master to decide if an apprentice should be removed from the team.

The skills of new journeymen will gradually increase. At first they should have only one apprentice. Over the months and years their increasing leadership skills will allow them to take two or three at a time. The most experienced Journeymen might play the role of master in smaller projects.

Attaining master status is no small feat. It requires the consensus of other masters, and must be demonstrated through several successful accomplishments.

I expect a journeyman would make $50-100K depending on their experience. I expect a master would make $150-$250K or more.

Now imagine a team of 13. One master, three journeymen, and nine apprentices. This is a powerful unit. Its size is right at the sweet spot for hyper productive teams. It has the right balance of experience. And… it’s pretty cheap. This team costs ~$600K per year, or about $50K per person. Or (consulting companies take notice) about $23/person/hour.

It seems to me that such a team could do much more, much better, than a team of 12 graduates lead by a tech-lead with five years experience. The productivity and efficiency (and efficiencies of scale!) of this approach should be obvious. Moreover, I think that being an apprentice on a team like this would provide a much better, much faster, and much cheaper education than a university degree. Finally, I think that using teams of this kind could be a remarkably cost-effective way to get very high quality software written very quickly.

Let's Hear it for the Zealots! 82

In his March 1st, 2009 column in SDTimes, Andrew Binstock takes the “Zealots of Agile” to task for claiming that Agile is the one true way. He made the counter-argument that non-agile projects have succeeded, and that agile projects have failed. He implied that the attitudes of the agile zealots are blind to these facts.

What a load of dingoes kidneys!

There is a difference between a zealot, and a religious fanatic. A religious fanatic cannot envision themselves to be wrong. We in the agile community may indeed be zealots, but we know we can be wrong. We know that projects succeeded before agile, and we know that agile projects have failed. We know that there are other schools of thought that are just as valid as ours. Indeed, most of us expect (even hope!) that agile will be superseded by something better one day.

Some of you may remember my keynote address at the 2002 XPUniverse in Chicago. My son, Micah, and I got up in front of the group dressed in Jiu Jistsu garb, and commenced to do a martial arts demonstration.

After the demonstration I made the point that a student of Karate could have given an equally spellbinding, though quite different, show. A student of Tae Kwon Do would amaze us with still other wonderful moves. The morale, of course, was that there are many ways to get the job done. There are many equally valid schools of thought.

However, the knowledge that there are other valid schools of thought does not dilute the zeal a student has for the school of thought he has chosen to study. Do you think that a Jiu Jistsu master isn’t a zealot? You’d better believe he is! To be great, one must have zeal. To rail against zeal is to rail against the desire for greatness. It is zeal that makes you go the extra distance to become great. The Jiu Jitsu master may respect the Karate master, but his goal is to become great at Jiu Jitsu.

So I think it is healthy that agile proponents are vociferous advocates of their school of thought. They are like Karate students who are excited about their new skills, and want to teach those skills to others. If their zeal to excel can infect others with similar zeal, so much the better. We need people in this industry who want to excel.

In his column Andrew derided agile zealots for claiming that Agile was the one true path. I don’t know of any prominent agile advocate who has ever made that claim. Indeed, when Kent Beck and I sat down in 1999 to plan out the XP Immersion training, we were very concerned that we might turn the XP movement into a religion. We did not want to create the impression that XPers were the chosen people and that wisdom would die with us. So we were, in fact, very careful to avoid any hint of the “one true path” argument.

As evidence of this, consider the Snowbird meeting in 2001. That meeting was inclusive, not exclusive. We invited people from all over the spectrum to join us there. DSDM, FDD, Scrum, Crystal, MDA, & RUP were all represented; and the agile manifesto (Yes, Andrew, Manifesto![1]) was the result. That manifesto was a simple statement of values, not a claim to deific knowledge.

Am I an Agile Zealot? Damned right I am! Do I think Agile is the best way to get software done? Damned right I do! I wouldn’t be doing Agile if I didn’t think it was best. Do I think Agile is better than someone else’s school of thought? Let me put it this way: I’m quite happy to go head to head against someone who follows another school of thought. I believe I’d code him right into the ground! Isn’t that what any good student of his craft would think? But I also recognize that one day I’ll lose that competition, and that will be a great day for me because it will give me the opportunity to learn something new and better.

Andrew also mentioned that Kent Beck and I are so obsessed with our “evangelical fervor” that we: “endlessly test and endlessly refine and refactor code to the point that it becomes an all-consuming diversion that does not advance the project”. WTF? I’ve been making monthly releases of FitNesse, and Kent has been cranking out releases of JunitMax; neither of us has been so busy gilding our respective lilies that we are failing to move our respective projects forward. Look around Andrew, we’re shipping code over here brother.

As part of his rant against our “evangelical fervor” Andrew asked this rather snide question: “I broke up that code into a separate class and added seven methods for what benefit, again?” This would appear to be a dig against refactoring – or perhaps excess refactoring. Still the question has a simple answer. We would only break up a module into a class with seven methods if that module was big, ugly, and complex, and by breaking it up we made it simple and easy to understand and modify. It seems to me that leaving the module in a messy state is irresponsible and unprofessional.

Andrew complains that there is very little Agile experience with projects over six million lines of code. I’m not sure where he got that number from, perhaps he’s been watching Steve Austin re-runs. Actually, the majority of my 2008 consulting business has been with very large companies with products well over six million lines of code. Agile-in-the-Large is the name of the game in those companies!

Finally, Andrew says Michael Feathers is a “moderate” Agile proponent. This is the same Michael Feathers who wrote a book defining Legacy code as code without tests – hardly a moderate point of view. Michael is a master, not a moderate.

I think Andrew has fallen into a common trap. He sees the zeal of the agile proponents and mistakes it for religious fanaticism. Instead of respecting that zeal as the outward manifestation of the inward desire to excel, he rails against it as being myopic and exclusive and then views all the statements of the agile proponents through that clouded viewport. Once you have decided that someone is a religious fanatic, it is difficult to accept anything they say.

I think standing against religious fanaticism in the software community is a good thing. I also think that those of us who are zealous must constantly watch that we are not also becoming blind to our own weaknesses and exclusive in our outlook. But I could wish that those who fear religious fanaticism as much as I do would stop confusing it with professional zeal.

So here’s the bottom line. People who excel are, by definition, zealots. People who aren’t zealous, do not excel. So there’s nothing wrong with being a zealot; indeed, zeal is a very positive emotion. The trick to being a zealot is to be mindful that the day will eventually come when some other zealot from a different school of thought will code you into the ground. When that happens, you should thank him for showing you a better way.

1 I kicked off the Snowbird meeting by challenging the group to write a “manifesto”. I chose the word “manifesto” because some years earlier I had read The Object Oriented Database System Manifesto and I thought it was a clever use of the word.

Quality: It's alive! It's ALIVE! 119

Recently James Bach wrote a compelling post entitled Quality is Dead. As much as I’d like to agree, something interesting has just happened that tempts me to believe in a rebirth.

Just when James finally declares the death of quality, along comes the Manifesto for Software Craftsmanship. This simple document that builds upon the four values declared in the Agile Manifesto went live late on Friday evening. Now, at 3PM on Saturday over 600 people have signed it!

What does this mean? I think it means that many of us have seen what James was talking about, and are tired of it. We don’t want our users posting blogs – as James did – crying that they HATE us. We want our users to be astonished by the elegance and simplicity of our creations. We want other software developers to look under the hood and be amazed and impressed at the clarity and simplicity they see.

We want to be proud of our work!

We want our quality back!

And so a few weeks ago some software developers gathered at the offices of 8th Light in Libertyville, Illinois, and began the process of creating this manifesto. There followed a very active and passionate discussion in the Software Craftsmanship email group. The end result was this manifesto.

I encourage all of you to read and sign the manifesto, join the email group, and help bring quality back to life in the software profession.

Whiners that Fail 155

The acronym is not accidental.

Recently, Michael Feathers posted a hugely valuable blog entitled: 10 Papers every Programmer should read at least twice. Do you have any idea how valuable this is? Michael has read hundreds, if not thousands, of papers, and he is freely offering his opinion about which ten are the best. A wise man would pay thousands of dollars for this information. But some people prefer to whine.

Get a load of this gem posted by someone named David:

... you should have actual pdfs of these papers, not links that require you to pay. If these papers were truly important, then you would be able to read them without paying … your tone is arrogant and annoying. Get over yourself.

Clearly this is a troll. Normally I do not feed the trolls. But this one pushed my buttons (I know, I know, that’s the intent of a troll—well it worked.) But it wasn’t only this response. Here’s another one by someone named Mik:

Thanks for the list, but please don’t link to ACM portal, it is a pay site. Always link to a free version if it is available. Yes, these papers are worth spending a minute or two searching for a free version, and yes they are probably worth spending real money to read as well, but if a free version exists, save us all the time and money and link to it.

One small moment for an author, or one giant waste of time for mankind.

What a bunch of whiners!

Here is this golden nugget laid in front of them, and they complain that it’s too heavy to pick up. Fools! Losers!

I’m sorry for the anger, but the attitude makes me crazy. Are we professionals who stand on our own and take responsibility for our careers? Or are we children who expect our parents to wipe our bums?

I know I’m preaching to the choir. The people who take the time to read this blog don’t generally need to be told this. But on the off-chance that this might actually reach someone and change their attitude…here goes.

YOU, and NO ONE ELSE, is responsible for your career. Your employer is not responsible for it. You should not depend on your employer to advance your career. You should not depend on your employer to buy you books, it’s great if they do, but it’s not really their responsibility. If they won’t buy them, YOU buy them! It’s not your employers responsibility to teach you a new language. It’s great if they send you to a training course, but if they don’t YOU teach the language to your self!

I fear greatly that our culture of entitlement has created a bunch of whining sissy programmers who think it’s unfair that they have to pay for a copyrighted article. (Pay? Who me? That’s my employer’s job! That’s my teacher’s job! That’s Michael Feathers’ job! I mean if they want me to be a good programmer then they’d better not expect ME to pay for these articles! They’d better not expect ME to do a google search for an article! They’d better come right over here to my cubicle between 9am and 10am and read the article to me while stroking my hair!)

The world does not owe you a living. Your employer does not owe you a career. And Michael Feathers’ does not owe you access to free articles.

Getting a SOLID start. 360

I am often asked: “How should I get started with SOLID principles?” Given the recent interest and controversy about the issue, it’s probably time I gave a written answer.

First things first.

You can read about the Solid principles here. This is a paper I wrote nearly a decade ago. It uses a somewhat dated form of UML, and examples are in C++. Also the concepts are severely abbreviated. This is the Cliff Notes. Still, it should give you an initial notion of the names, definitions, and concepts.

There are quite a few papers here that explain the principles in much more detail. Just click on the “Design Principles” topic to see them all. Though I think you’ll find the other topics pretty interesting too.

Finally, the principles are definitively described in two books: Agile Software Development: Principles, Patterns, and Practices, and Agile Principles Patterns, and Practices in C#. You can see descriptions of these books here

What do I mean by “Principle”

The SOLID principles are not rules. They are not laws. They are not perfect truths. The are statements on the order of “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.” This is a good principle, it is good advice, but it’s not a pure truth, nor is it a rule.

The principles are mental cubby-holes. They give a name to a concept so that you can talk and reason about that concept. They provide a place to hang the feelings we have about good and bad code. They attempt to categorize those feelings into concrete advice. In that sense, the principles are a kind of anodyne. Given some code or design that you feel bad about, you may be able to find a principle that explains that bad feeling and advises you about how to feel better.

These principles are heuristics. They are common-sense solutions to common problems. They are common-sense disciplines that can help you stay out of trouble. But like any heuristic, they are empirical in nature. They have been observed to work in many cases; but there is no proof that they always work, nor any proof that they should always be followed.

Following the rules on the paint can won’t teach you how to paint.

This is an important point. Principles will not turn a bad programmer into a good programmer. Principles have to be applied with judgement. If they are applied by rote it is just as bad as if they are not applied at all.

Having said that, if you want to paint well, I suggest you learn the rules on the paint can. You may not agree with them all. You may not always apply the ones you do agree with. But you’d better know them. Knowledge of the principles and patterns gives you the justification to decide when and where to apply them. If you don’t know them, your decisions are much more arbitrary.

So how do I get started?

“There is no royal road to Geometry” Euclid once said to a King who wanted the short version. Don’t expect to skim through the papers, or thumb through the books, and come out with any real knowledge. If you want to learn these principles well enough to be able to apply them, then you have to study them. The books are full of coded examples of principles done right and wrong. Work through those examples, and follow the reasoning carefully. This is not easy, but it is rewarding.

Search your own code, and the code of others, for applications and violations of the principles. Determine whether those applications and violations were justified. Improve the designs by applying one or more principles, and see if the result is actually better. If you’d like to study a code base that was written by people who’ve been immersed in these principles for years, then download the source for FitNesse from fitnesse.org.

Conduct or join a discussion group at work. Do brown-bags, lunch-n-learns, reading-groups, etc. People who learn in groups learn much more, and much more quickly, than people who study alone. Never underestimate the power of the other guy’s viewpoint.

By the same token, join a user group with people from different companies. Attend monthly meetings and listen to the speakers, or participate in the discussions. Again, you’ll learn an awful lot that way.

Practice, practice, practice, practice. Be prepared to make lots of mistakes.

And, of course, apply what you’ve learned on the job, and ask your peers to review your work. Pair program with them if at all possible. “As iron sharpens iron, so one man sharpens another.” (Proverbs 27:17)

An Open Letter to Joel Spolsky and Jeff Atwood 203

Joel, Jeff,

Here is an open letter to the two of you that I hope we can use in our upcoming StackOverflow #40 podcast. I won’t post it on my blog until we’ve been able to iterate it a bit. I’ve spent several hours on this trying to balance the tone. It used to be a lot longer <grin>.

Dear Joel and Jeff

In the Stack Overflow Podcast #38 you said: “Last week I was listening to a podcast on Hanselminutes, with Robert Martin talking about the SOLID principles … they all sounded to me like extremely bureaucratic programming that came from the mind of somebody that has not written a lot of code, frankly.”

And again later: ”...it seems to me like a lot of the Object Oriented Design principles you’re hearing lately from people like Robert Martin and Kent Beck and so forth have gone off the deep end into architecture for architecture’s sake.”

And yet again: “People that say things like this have just never written a heck of a lot of code.”

And still again: “One of the SOLID principles, (a butchering of the Single Responsibility Principle) and it’s just… idiotic! You can’t build software that way!”

I hope you’ve had time to perform a little due diligence since then, and that you now realize that your statements were unfair, harmful, and were pretty much crap.

I understand that you were trying to make a valid point and that the words just got away from you a bit. I quite agree that a dogmatic or religious application of the SOLID principles is neither realistic nor beneficial. If you had read through any of the articles and/or books I’ve written on these principles over the last 15 years, you’d have found that I don’t recommend the religious or dogmatic approach you blamed me for. In short, you jumped to a erroneous conclusion about me, and about the principles, because you weren’t familiar with the material.

I understand that this was a podcast, and that you were both just jawing. However, your podcasts are a product that you ship to everyone in the world. The content of that product can do great good; but it can also do great and permanent harm. One would think that you’d want to be careful with such a product. Yet in the intensity of the moment you got a bit careless and spewed some crap instead. That’s fine, everybody makes mistakes. But then you shipped it! You shipped a product that had a huge bug in it. You should have had tests!

Could it be that when you said ”...quality just doesn’t matter that much…” you were being serious. Clearly the quality of podcast #38 didn’t matter much to you, since you shipped it without verifying that your information was accurate. As a result, you did unjust harm to me. Were I a more litigious person, we might be having this discussion in court.

Now I’m quite certain that you don’t want to ship bad product. I just think that you’ve been careless with your production process. You haven’t put in place a mechanism that will stop you from shipping crap. So I suggest that you practice Test Driven Development with your podcast. Write down the acceptance criteria beforehand (I suggest lawsuit avoidance would be a high priority), and then review the product against those criteria afterwards. Yes, this will take some time, and there will be a cost. However, it will pay back handsomely because your product will be far better, and you will avoid embarrassments like this one (or worse). And, after all, products deserve and require this kind of care. So do your listeners. This is just simple professionalism. Don’t ship shit. —-——-

Some of the other points we could talk about in the podcast:

- TDD for real this time. You guys can just throw your complaints at me and I’ll address them. * For example, I’d like to explain how one would test Joel’s JPeg compression feature.

- ISP and SRP, the two principles that Joel butchered.

- Mike Connie’s observation (in #39) about interfaces.

- How, when, and why to apply Principles and Patterns.

- From Stack Overflow: * Large Switch statements: Bad OOP? * JSON is used only for JavaScript? (Rant on XML) * ASP.Net – How to effectively use design patterns without over-engineering!

Speed Kills 112

Ron Jeffries wrote a wonderful blog about how we kid ourselves that there is a tradeoff between quality and speed. Isn’t there?

That depends on what you mean by “speed”. If you mean rushingtogetawholebunchofshitcodedandsortofrunning, then quality is not for you. On the other hand, if by “speed” you mean delivering working software quickly and repeatably release after release after release; then maintaining high quality is your only option.

The first course is that of the adrenline junkie. The hacker stereotype of the twinkie eating cola guzzling nerd who cackles like the Wicked Witch of the West while tunnel visioning into his screen and keyboard. The second course is that of the professional programmer, the craftsman who with calm demeanor and deliberate confidence servers his clients, and his career.

We all feel the pressure to rush. It’s like a drug, really. It feels good to through off the disciplines and justcodeupawholebunchofshit. We get the adrenline high, and we feel as though we are skating on the edge between success and failure, sailing so close to the wind that we’re on the verge of tipping, getting the rush of speed. When we get our code working we feel victorious!.

What we should be feeling is stupid. Because we actually were skating on the edge between success and failure. We should not feel victorious, we should feel shame.

We justify this addiction to speed by telling ourselves that our bosses want us to go fast. We tell ourselves that time-to-market requires that we sail close to the wind. And then we put the needle in our arm and let fly another dose of speed—oblivious to the consequences.

I teach a lot of programming classes in which I give the students programs to write. I tell them that the goal is not to finish the programs, but to learn the skills of programming. I tell them that the code they are writing will all be deleted after they leave. I tell them to focus on the techniques and disciplines they are learning, not on finishing the programs. And yet on Friday afternoon there are always a group of folks who are flailing away at their keyboards trying desperately to finish something that they know will be deleted as soon as they leave.

These people have surrendered to the drug of speed. They need to conquer. They manufactured their own deadline pressure and behaved as if their boss was breathing down their necks.

How do you really get things done quickly? You listen to your grandparents. Remember what they told you? “Slow and steady wins the race.” and “Anything worth doing is worth doing well.” How does a professional craftsman get things done quickly? He/she adopts an attitude of calm, focuses on the problem to be solved, and then step by step solves that problem without rushing, without yielding to the need for speed, without surrendering to the desire for a quick conquest.

When you feel the temptation to rush, resist it. Leave the keyboard and walk around. Distract yourslef with something else. Do not give in to the call of your addiction.

If you want to be a craftsman. If you want to be someone who builds software quickly, accurately, and repeatably. If you want to be someone that your employer respects and values. If you want to respect yourself. Then remember this simple fact. Speed Kills.

Multi-dimensional Seniority 211

I was at a meeting of the Chicago Software Craftsmanship group last night. Dave Hoover and Paul Pagel were talking about the different apprenticeship models at Obtiva and 8thLight.

The 8thLight model uses a 90 day probation period during which an “apprentice” has an appointed mentor who guides the apprentice to learn enough to become a “craftsman”.

The Obtiva model is less structured, but there’s no probationary period. Once an apprentice had delivered something meaningful for a client, and had been recognized by the others, he/she would become a “consultant”, and eventually a “senior consultant”

Both speakers used the term “journeyman” but neither defined it. Both speakers agreed that 90 days, or a year, or even two years was insufficient for an apprentice to become a true journeyman.

After the talk I started to ponder this question of seniority. What makes a software developer senior? Certainly the amount of time spent in a career is a big factor. Someone with 15 years of experience is certainly senior.

However, there’s that old joke about the guy who had 15 years of experience, the same year fifteen times in a row. That’s a real concern. It is perfectly possible to work for 15 years and dig yourself into a rut you can’t get out of. Think of all those Cobol programmers who never learned anything else.

Both Paul and Dave talked about how they planned for their apprentices to grow with the company. They both lamented apprentices that had left the company to do other things.

This made me think about the apprentices we’ve had at Object Mentor. (Paul was one of them. Dave was almost another.) Over the years we’ve had seven or so apprentices. Today, we have none. Not a single apprentice has stayed at Object Mentor. Is this bad?

It hasn’t been bad for the apprentices. Two went on to form their own company (8thLight). Others have made names for themselves in the community. More than one has written a book. Nearly all are passionate craftsmen who care about their profession, and who are making an impact.

It wasn’t bad for Object Mentor either. The apprentices moved on when it was a good time for them to move on, and we have kept good relationships with them. More than one customer has come our way because of referrals from past apprentices.

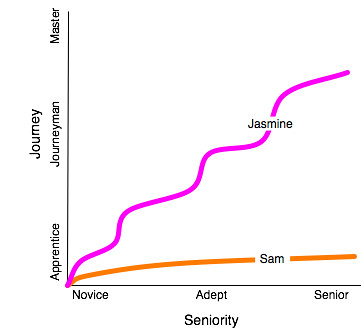

So at the end of the meeting, when everyone had milled away from the central area, I went to the whiteboard and scratched out a simple diagram. It was an graph with Seniority on the horizontal axis, and Journey on the vertical axis.

Then I drew a nearly horizontal line starting from the origin and hugging the Seniority axis. This is the career path of the guy who has the same year of experience 15 times in a row. Let’s call him Sam. Then I drew another line which was a stair-step that went towards the upper right at something less then a 45 degree angle. This is the career path of a developer who changes jobs a few times during his/her career. Let’s call her Jasmine.

I don’t think there is a vertical path. The only way to go on a journey is to spend some time at it, and that drives you horizontally.

OK, now maybe I’ve just spent a dozen paragraphs explaining the obvious. To-wit: A journeyman is a journeyman because he/she’s gone on a journey. Does that journey have to involve changing employers? I think it probably does. You see, there’s a problem.

The student/teacher relationship is persistent. At least in my experience it is. The only way for a teacher and student to ever consider themselves to be peers is for the relationship to break and then reform later in a new context.

Sam, has remained an apprentice, even though he’s got lots of experience. Why? Because he still works with his original mentors who consider him to be their student. Jasmine, on the other hand, has seen the world, experienced many different situations in many different places. She could become a master.

OK, ok. I’m belaboring the point. So let me conclude. If you are considering an apprenticeship program it seems to me that the most important aspect of that program is that the relationship is temporary, and results in a journey. In other words, don’t expect to hold on to your apprentices for very long.

Fudge anyone? 76

Back in September, when I was just staring the Slim project, I made a crucial architectural decision. I made it dead wrong. And then life turned to fudge…

The issue was simple. Slim tables are, well, tables just like Fit tables are. How should I parse these tables? Fit parses HTML. FitNesse parses wiki text into HTML and delivers it to Fit. Where should Slim fit in all of this?

Keep in mind that Fit must parse HTML since it lives on the far side of the FitNesse/SUT boundary. Fit doesn’t have access to wiki text. Slim tables, on the other hand, live on the near side of the FitNesse/SUT boundary, and so have full access to wiki text, and the built in parsers that parse that text.

So it seemed to me that I had two options.

- Follow the example of Fit and parse wiki text into HTML, and then have the Slim Tables parse the HTML in order to process the tables.

- Take advantage of the built in wiki text parser inside of FitNesse and bypass HTML altogether.

I chose the latter of the two because the Parsing system of FitNesse is trivial to use. You just hand it a string of wiki text, and it hands you a nice little parse tree of wiki widgets. All I had to do was walk that parse three and process my tables. Voila!

This worked great! In a matter of hours I was making significant progress on processing Slim decision tables. Instead of worrying about parsing HTML and building my own parse tree, I could focus on the problems of translating tables into Slim directives and then using the return values from Slim to colorize the table.

Generating html was no problem since that’s what FitNesse does anyway. All I had to do was modify the elements of the parse tree and then simply tell the tree to convert itself to HTML. What a dream.

Or so it seemed. Although things started well, progress started to slow before the week was out. The problem was that the FitNesse parser is tuned to the esoteric needs of FitNesse. The parser makes choices that are perfectly fine if your goal is to generate HTML and pass it to Fit, but that aren’t quite so nice when you’re goal is to use the parse tree to process Slim tables. As a simple example, consider the problem of literals.

In FitNesse, any camel case phrase fits the pattern of a wiki word and will be turned into a wiki link. Sometimes, though, you want to use a camel case phrase and you don’t want it converted to a link. In that case you surround the phrase with literal marks as follows: !- FitNesse-!. Anything between literal marks is simply ignored by the parser and passed through to the end.

Indeed, things inside of literals are not even escaped for html! If you put <b>hi</b> into a wiki page, it will escape the text you’ll see <b>hi</b> on the screen instead of a bold “hi”. On the other hand, if you put !- <b>hi</b>-! on a page, then the HTML is left unescaped and a boldfaced “hi” will appear on the screen.

I’m telling you all of this because the devil is in the details—so bear with me a bit longer.

You know how the C and C++ languages have a preprocessor? This preprocessor handles all the #include and #define statements and then hands the resulting text off to the true compiler. Well, the wiki parser works the same way! Literals and !define variables are processed first, by a different pass of the parser. Then all the rest of the wiki widgets are parsed by the true parser. The reason that we had to do this is even more devilishly detailed; so I’ll spare you. Suffice it to say that the reasons we need that preprocessor are similar to the reasons that C and C++ need it.

What does the preprocessor do with a literal? It converts it into a special widget. That widget looks like this: !lit?23? What does that mean? It means replace me with the contents of literal #23. You see, when FitNesse sees !- FitNesse-! it replaces it with !lit?nn? and squirrels FitNesse away in literal slot nn. During the second pass, that !lit?nn? is replaced with the contents of literal slot nn. Simple, right?

OK, now back to SLIM table processing. There I was, in Norway, teaching a class during the day and coding Slim at night, and everything was going just great. And then, during one of my tests, I happened to put a literal into one of the test tables. This is perfectly normal, I didn’t want some camel case phrase turned into a link. But this perfectly normal gesture made a unit test fail for a very strange reason. I got this wonderful message from junit: expected MyPage but was !lit?3?

I knew exactly what this meant. It meant that the value MyPage had been squirreled away by the first pass of the parser. I also knew that I had utterly no reasonable way of getting at it. So I did the only thing any sane programmer would do. I wrote my own preprocessor and used it instead of the standard one. This was “safe” since in the end I simply reconvert all the colorized tables back into wiki text and let the normal parser render it into HTML.

It was a bit of work, but I got it done at one am on a cold Norwegian night. Tests passing, everything great!

Ah, but no. By writing my own preprocessor, I broke the !define variable processing – subtly. And when I found and fixed that I had re-broken literal processing – subtly.

If you were following my tweets at the time you saw me twitter ever more frantically about literals. It was the proverbial ball of Mercury. Every time I put my thumb on it1 it would squirt away and take some new form.

I fell into a trap. I call it the fudge trap. It goes like this:

forever do {“I can make this work! Just one more little fudge right here!”}

I was in this trap for two months! I was making progress, and getting lots of new features to work, but I was also running into strange little quirks and unexpected bizarre behaviors caused by the fudging I was doing. So I’d fudge a little more and then keep working. But each little fudge added to the next until, eventually, I had a really nasty house of cards (or rather: pile of fudge) ready to topple every time I touched anything else. I started to fear my own code2. It was time to stop!

I knew what I had to do. I had to go back to my original architectural decision and make it the other way. There was no escape from this. The FitNesse parser was too coupled to the wiki-ness, and there was no sane way to repurpose it for test table processing.

I dreaded this. It was such a big change. I had built so much code in my house of fudge. All of it would have to be changed or deleted. And, worse, I needed to write an HTML parser.

I was lamenting to Micah about this one day in late November, and he said: “Dad, there are HTML parsers out there you know.”.

Uh…

So I went to google and typed Html Parser. Duh. There they were. Lots and lots of shiny HTML parsers free for the using.

I picked one and started to fiddle with it. It was easy to use.

Now comes the good part. I had not been a complete dolt. Even when I was using the FitNesse parse tree, I ate my own dogfood and wrapped it in an abstract interface. No part of the Slim Table processing code actually knew that it was dealing with a FitNesse parse tree. It simply used the abstract interface to get its work done.

That meant that pulling out the wiki parser and putting in the HTML parser was a matter of re-implementing the abstract interface with the output of the new parser (which happened to be another parse tree!). This took me about a day.

There came a magic moment when I had both the wiki text version of the parser, and the HTML version of the parser working. I could switch back and forth between the two by changing one word in one module. When I got all my tests passing with both parsers, I knew I was done. And then the fun really began!

I deleted ever stitch of that wiki parse tree pile of fudge. I tore it loose and rent it asunder. It was gone, never to darken my door with it’s fudge again.

It took me a day. A day. And the result is 400 fewer lines of code, and a set of Slim tables that actually work the way they are supposed to.

Moral #1: “Fudge tastes good while you are eating it, but it makes you fat, slow, and dumb.”

Moral #2: “Eat the damned dog food. It’ll save your posterior from your own maladroit decisions.

1 I do not recommend that you actually put your thumb on any Mercury. Never mind that I used to play with liquid Mercury as a child, sloshing it around from hand to hand and endlessly stirring it with my finger. Wiser heads than I have determined that merely being in the same room with liquid Mercury can cause severe brain damage, genetic corruption, and birth defects in your children, grandchildren, and pets.

2 Fearing your own code is an indicator that you are headed for ruin. This fear is followed by self-loathing, project-loathing, career-loathing, divorce, infanticide, and finally chicken farming.

Hudson -- A Very Quick Demo 474

I recently set up Hudson as the continuous integration server for FitNesse. I was impressed at how very very simple this was to do. The Hudson folks have adopted the same philosophy that we adopted for FitNesse: download-and-go.

So I recorded a quick (<5min) video showing you how I set this up. In this video you'll see me start Hudson from scratch, create the job to build FitNesse, and then run the FitNesse build.

Hudson—A Very Quick Demo from unclebob on Vimeo.